Interactive Parallel Content to Support Analytical Skills in a Large Online Course

ITALIAN 2055 – Mafia Movies is a GE Literary, Visual and Performing Arts Foundations Course. As part of the expected learning outcomes, students develop skills in analyzing and interpreting cinematic artworks, while also evaluating the mutual relationship and influence between culture and artistic ideas and practices. The Midterm and Final exams in this course specifically evaluate the students’ ability to conduct thorough scene analyses. Such analyses involve the identification of the specific film techniques employed within individual scenes and the explanation of how those techniques reflect and discuss important cultural issues such as gender, politics, and the representation of crime in the case of the Italian Mafia.

During the AU21 semester, the course instructor and graders noted that, while students were generally able to summarize the most salient points of a course reading or the cultural issues at play and they could also identify and list the more obvious film techniques within a particular scene, many students struggled with higher-order skills. In both the exam essays and in discussion board posts, students struggled to connect the film techniques that they identified to the cultural issues addressed in the readings or in the synchronous class sessions.

In the space of the synchronous, large class environment, the time allotted to comprehensively exploring the process of a scene analysis was limited, generally to a single synchronous session during the first week of the semester. During this individual session the instructor conducts a short scene analysis with the entire class, utilizing short clips from two different prominent films in Italian cinema. But because of the large class size and time limitations, opportunities for individual support regarding the understanding of this process are scarce. To help bolster such support for students, the incorporation of asynchronous parallel content that could chunk and scaffold the scene analysis process while also providing immediate feedback to learners seemed vital to improving their ability to make the connection between cinematic techniques and broader historical, political, and cultural concerns.

To create this asynchronous parallel content, I started by thinking about how we could employ principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and User Experience Design for Learning (UXDL) to enhance existing course materials to better guide the development of these analytical thinking skills. The strategies from these frameworks that I relied on most include:

- Chunking of information to help guide learners through the individual steps of the scene analysis process.

- Maximizing transfer and generalization by organizing and scaffolding steps and activities and by incorporating explicit opportunities for low-stakes practice.

- Providing multiple means of representation to ensure that learning materials and the overall experience were accessible, inclusive, and engaging for as many students as possible.

- Incorporating immediate and relevant feedback so that students had an opportunity in the asynchronous environment to reflect on their learning and check their understanding and progress.

To implement each of these strategies, I broke down and incorporated the existing materials into three separate interactive activities to be completed in sequential order:

- a technical introduction to film language,

- an introduction to formal scene analyses, and

- a final formal scene analysis practice exercise.

An H5P interactive book was created for each individual exercise to further chunk the materials utilizing individual chapters that contain a variety of text, multimedia, and quizzing elements.

Chunking Information to Reduce Cognitive Overload

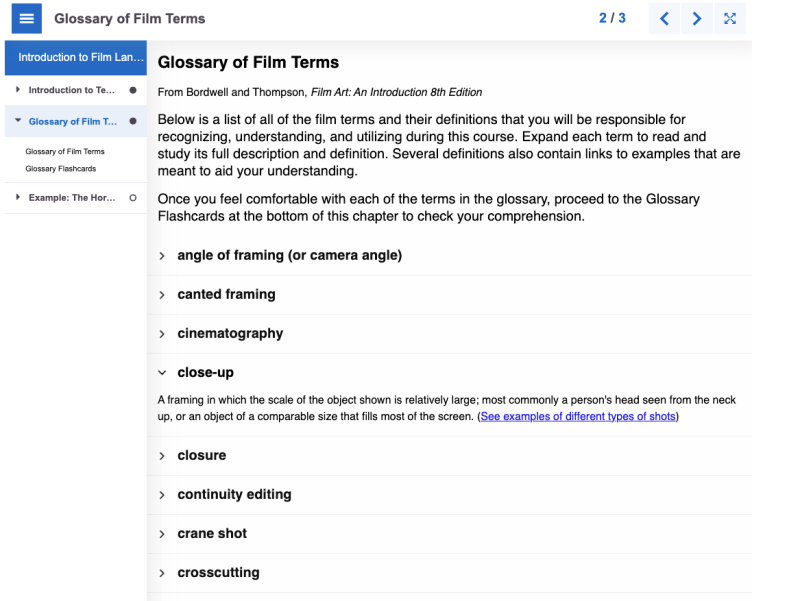

The first step to conducting a scene analysis involves familiarity with shared language. In previous semesters, students were given these terms and definitions by way of a multi-page PDF document, but they were only responsible for understanding and recognizing a select portion of that list.

In the first interactive exercise that focuses on film language, I began by curating a list of the required terms only. Removing the optional terms from the list helped to reduce cognitive overload and maintain focus on the most important pieces of information. With this curated list in hand, I then utilized H5P’s accordion feature within the interactive book to further minimize the amount of information and text that students would see at any one time. Their first experience with the language was via a simple list of terms that could then be expanded one at a time to view the full definition. As part of these definitions, links to visual examples, where possible, were also provided to help clarify meaning.

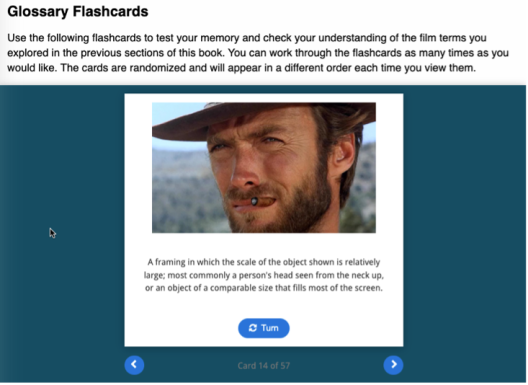

While the accordions help to minimize distractions and maximize focus on the most important terms for the course, the vertical list may still have felt overwhelming to some. In order to provide additional means of representation, the same list of terms was incorporated into a randomized set of flashcards where a single term is released, one at a time, aiding in the reduction of cognitive overload while also providing additional support for recall.

Guiding Information Processing

After the film language introduction, students then move on to the second interactive activity where they are introduced to the steps of a formal scene analysis. The scene analysis is generally made up of three principal steps:

- Watching the film in its entirety while making observations and taking notes.

- Conducting a double-take where the viewer rewatches specific scenes (often several times) and makes a list of any and all film techniques used.

- Analyzing and interpreting how those techniques speak to the broader story of the film.

Each of the three steps listed was organized into individual chapters within the H5P interactive book, the details of which are described below.

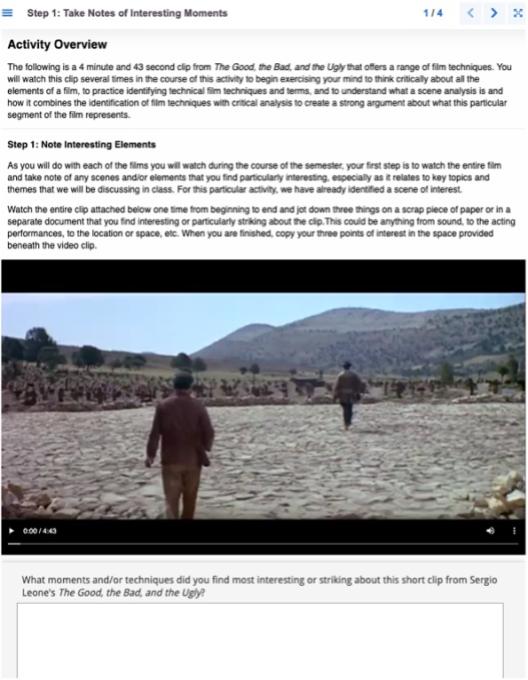

In chapter 1 or step 1, students are prompted to watch an unaltered film clip in its entirety and take notes on anything and everything that they find interesting, including sound, visuals, dialogue, etc. A text entry space is included directly below the video to provide a space for note-taking, but to offer some autonomy to the learner, they are informed that they can also take notes on a separate sheet of paper or in any other platform of their choosing.

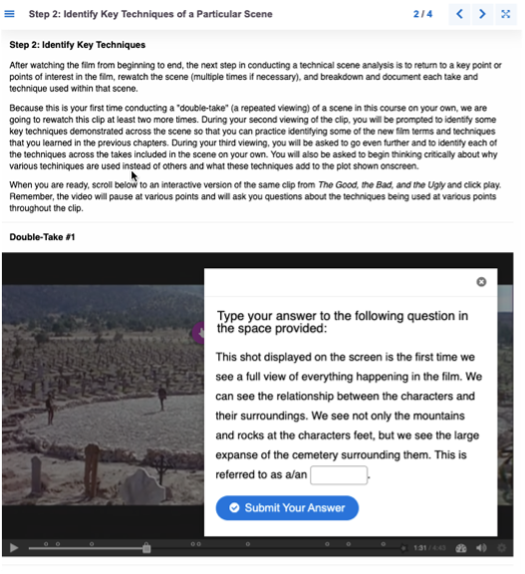

Following initial observation, the second chapter of the book includes the same video clip as the first chapter, but transforms it into an interactive video, incorporating elements such as multiple-choice questions, fill-in the blank questions, and timeline bookmarks. The multiple choice and fill-in-the-blank questions appear immediately following the occurrence of a specific technique, automatically pausing the video and forcing the learner to focus on a singular moment in the timeline. Students are then asked to identify a film technique that they just witnessed. Using the check button, they receive immediate feedback about the correctness of their answer and, in some instances where they answered incorrectly, they may receive additional hints to point them in the right direction. In addition to offering this immediate feedback, students have the ability to retry a question or even the entire activity as many times as they would like, encouraging additional practice and exploration.

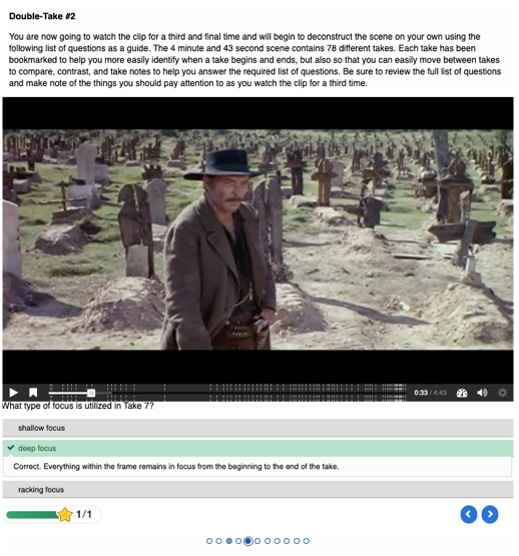

The third and final technical exercise takes this step a bit further than the second. An additional double-take activity is added within step 2 of the third exercise to further scaffold and develop students’ identification skills. In this second task, bookmarks are added to the video timeline, identifying each individual take within the clip and highlighting visual patterns related to the frequency and length of each take. This version of the video is then followed by a brief quiz question set that asks learners to focus their attention on just two of the 78 individual takes that appear during the clip, practicing the ability to focus on more granular details and the connections between them.

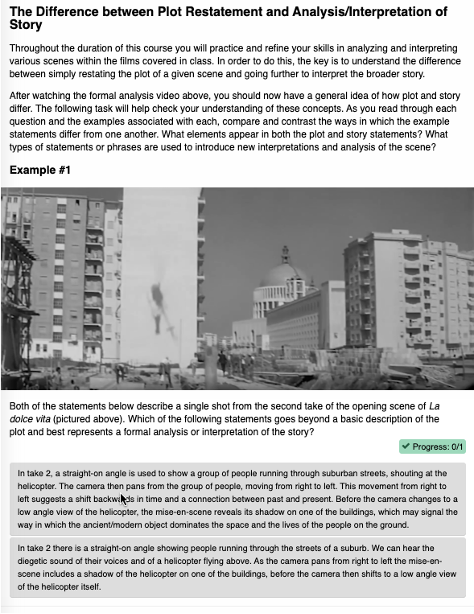

The final step of the scene analysis process is to analyze and interpret the broader story of the film. Naturally, this tends to be the most challenging step for students to master. In grading the exams, there was a clear gap in students’ understanding of the difference between simply restating the plot (all the events that are directly presented to the viewer) and interpreting the story (all the events that the viewer sees and hears, plus all those that the viewer infers or assumes). To help support students’ understanding of this crucial difference, scaffolding and template examples were used to help build comprehension.

In the second exercise, the step 3 analysis task focuses on simple recognition of plot vs. story. Students are given examples of two written descriptions of an individual take within the film clip. Each of the descriptions incorporates film terminology, but one example demonstrates a restatement of the plot, while the second exhibits an interpretation of the story. Students are asked to read each description and identify which is which.

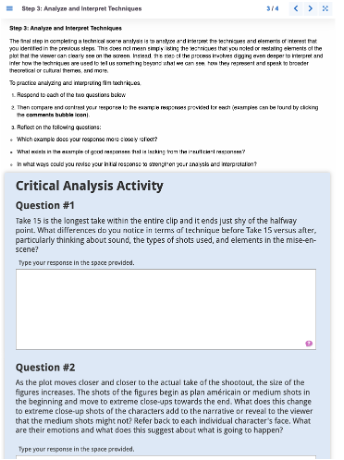

In the third exercise, step 3 asks students to recognize the difference between plot and story through concrete textual examples. This time, however, rather than simply identifying plot vs. story, students are asked to try their hand at writing their own analysis. To help guide this sort of thinking and writing they are given very specific prompts to help point out critical changes in techniques that often lead to these deeper interpretations.

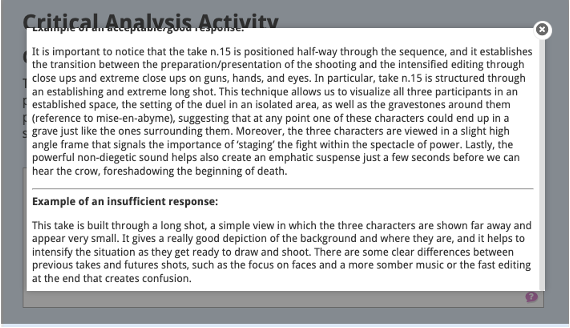

Because this task involves open-ended responses, it is harder to provide immediate feedback as the possible “correct” answers are somewhat limitless. Yet feedback at this point in the process is essential. In order to provide an opportunity for feedback and reflection, examples of both acceptable/good responses and insufficient responses to the prompt are given to the learner within interactive buttons at the bottom of the text entry box. The specific instructions for this writing task direct the learner to compare and contrast the analysis that they have just written to the examples provided, using pointed cues and prompts to draw attention to critical differences between the two examples. The prompt specifically asks the learner to:

- Determine which of the two examples their own analysis more closely reflects.

- Compare and contrast the elements that differentiate the acceptable response from the insufficient one.

- Reflect on how they could specifically revise what they have written utilizing the differentiating elements that they just noted to further strengthen their own interpretation.

While qualitative feedback has yet to be collected from the students, some initial quantitative feedback over the course of three semesters shows promising results. There seems to be some suggestion that students’ participation in these low-stakes activities does, in fact, have a positive impact on Midterm and Final Exam scores. In particular, those who complete both of the scene analysis exercises versus those who complete only the initial introduction to scene analysis exercise average higher scores on the exams.