Office of Distance Education Instructor Spotlight: Dr. J.T. Eisenhauer Richardson

This installment of ASC ODE's Instructor Spotlight series features Dr. J.T. Eisenhauer Richardson.

Dr. J.T. Richardson is an Associate Professor in the Department of Arts, Administration, Education and Policy. In addition, Dr. Richardson is the Faculty Director of the Online M.A. in Art Education Program and the incoming Chair of the Graduate Studies Program. Their research and teaching critically frame constructs of normalcy and reimagine inclusive practices, curriculum, and places of learning informed by critical disability studies. They serve as the current Chair of the Disability Studies in Art Education Interest Group of the National Art Education Association. Their scholarship in books and journals including Studies in Art Education, Art Education, Disability Studies Quarterly, International Review of Qualitative Research, Contemporary Art and Disability Studies, and the Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies.

To gain a clearer picture of Dr. Richardson as an instructor, especially one who thinks about distance education, we posed several questions to them about their opinions and takeaways from online teaching, as well as any advice they might share with other instructors who may be similarly invested.

I do not approach distance education in terms of replacing or replicating in-person learning experiences but instead building from what is distinctive about distance education. While I recognize distance learning and in-person courses as having distinct strengths and capabilities, I also recognize what I learn about course design, teaching, and learning in distance education or in-person learning environments as mutually informative.

Within higher education, I recognize distance education’s contributions to existing commitments, including accessibility, developing learning experiences responsive to the diverse needs of today's students, developing innovative curricula and approaches to teaching, enhancing student engagement, and fostering opportunities for collaboration.

Regarding Accessibility...

Access and flexibility are central to distance education enabling students that would otherwise not be able to access on-campus resources and opportunities to take courses and complete degrees or certificates. For example, many of the students in our Online MA degree program work full-time and need the flexibility of asynchronous learning. However, there are also multiple accessibility considerations across in-person and online courses. We need to continue finding ways to address questions surrounding access and higher education. Accessibility emphasizes designing flexible and responsive courses that begin by anticipating the many ways in which students learn, interact with content, engage with others, and may experience a particular learning environment. Access is informed by a sense of belonging within learning communities and responsive class environments.

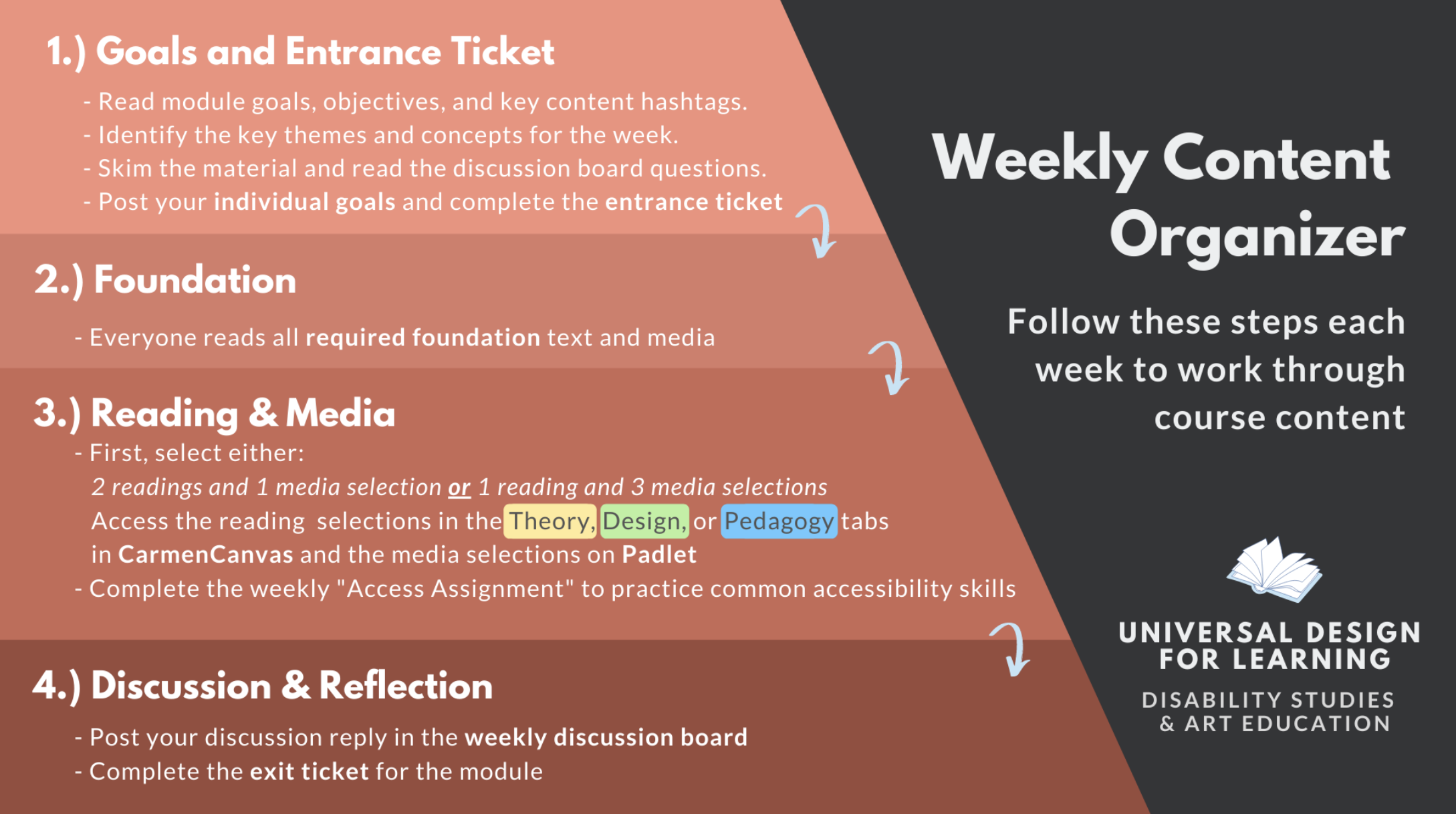

Image caption: Graphic created by Megan Wanttie

Regarding Engagement...

Some concerns raised about distance education surround student participation, engagement, and social connection. However, many in-person classes do not foster participation and connection solely because they are in-person. Barriers impacting student learning in distance learning and in-person spaces are often the result of unquestioned beliefs about learning, students, and participation that create barriers.

Participation, engagement, communication, and the social dimensions of education are frequently areas in which we carry presumptions about effective teaching and learning that may be exaggerated in an online environment. However, in-person environments also privilege particular types of learners. For example, suppose I assume that quality participation and understanding are demonstrated by being actively engaged during in-person discussions twice a week at 9 AM. I may privilege those students who excel at this type of verbal communication and social engagement.

Conversely, those less inclined to participate in class discussions are not necessarily unprepared or lack an understanding of the content. Many factors enter a class discussion such as how one experiences that environment, how discussions are organized, the social dynamics in the room, and more. However, some students thrive in online asynchronous “discussions” because they have time to plan what they want to say, write rather than speak, work in a different physical environment, and more. Recognizing these differences, I approach the design of my in-person and online courses by considering how to incorporate multiple forms of communication, participation, engagement with content, and ways to demonstrate learning. I incorporate tools and participation strategies that I developed for my online courses to create more options for student success within my in-person course designs.

Students and instructors often have less-ideal experiences in distance-learning courses that attempt to replicate in-person teaching approaches. Interestingly, while the tendency is more often to question distance learning, I would suggest that distance education reveals the limitations of common in-person teaching and learning approaches. For example, suppose my solution for the online version of my lecture course is to create a mandatory 40-minute Zoom lecture at 9 AM on Tuesdays and Thursdays. In that case, the limitation I am encountering is likely not simply Zoom but the limitations of on-line lectures. Students sitting together listening to a lecture on campus are not necessarily more engaged and actively learning than those with their cameras off. Therefore, what I consider is what I already know is a limitation or challenge with a course as an opportunity to reimagine the course design using different modalities and instructional strategies. How might I incorporate different media types, reflection activities, self-assessments, and peer work beyond repeating what I already know to be the limitations of my current lecture model to create a more engaging learning experience?

In my first year as an Assistant Professor at Ohio State, I collaborated with another faculty member to develop a course for our online MA in Art Education Program. This was the first online MA degree program in the College (which later became ASC) and was one of the first in our field. Distance education has been a part of my work at Ohio State for many years. My participation in this program has been integral in better understanding the needs of current teachers in K-12 and community settings and developing a deeper understanding of course design and the needs of adult learners.

To fully realize the potential of distance education, we may need to reframe our understanding of what we mean by “distant.” What are students “distant” from? One aspect of our online MA in Art Education program is how we integrate the intersection of our students' professional roles and their communities throughout the program. General goals in education across disciplines involve a student's ability to apply what they know to make meaningful connections between what they learn and their own lives and experiences. Likewise, we strive to foster more meaningful collaborations and partnerships with communities as a university. The courses that I teach bring together professionals working in different communities across Ohio and nationally. Understanding that students come together rather than remain distant is vital for successful online learning experiences. Our students continue to work within their communities while also being part of the learning community we foster across the degree program. However, this ability to foster higher education learning spaces that are more directly engaged with students’ communities and experiences points to further opportunities for innovation. We can expand our idea of distance education beyond traditional degree program frameworks to cultivating community and collaborative practices that bring individuals together from diverse areas to develop meaningful ways to address collective concerns. What we learn from effective distance education programs and forms of engagement can also inform strategies for developing meaningful and authentic partnerships between the University and communities in Ohio and nationally.

We also consider how to engage students at the level of experimenting with the familiar things that surround them in new ways. For example, I teach an artmaking course in which the students, mainly practicing teachers, engage with everyday materials in their environments. This course was designed before COVID-19 and necessitated many teachers to arrive at similar creative strategies for working with K-12 students at home and with varying access to materials. However, the ability to creatively engage with everyday materials in one's home and the neighborhood enables teachers and students to think beyond what they already know or assume about artmaking. As a result, students' and teachers' discover different ways of thinking about artmaking, a willingness to play, and to take chances to emerge in new ways.

As I described earlier, I believe that distance education and online course design work best when we do not simply replicate in-person courses when we design distance education experiences.

Throughout our Online MA in Art Education program, we emphasize forming learning communities online. Here our students reflect on their professional practices and benefit from learning about the challenges and strategies of others in the class and share their reflections on course materials in relation to their individual professional contexts.

In a recent graduate-level course related to disability studies in art education and universal design for learning, I collaborated with a course designer from ODEE and AAEP graduate students to create an online course that modeled critical accessibility and universal design for learning. There were several things I wanted to improve upon in revising the existing course. I wanted the course to model, rather than simply present, content relating to critical accessibility, digital accessibility, and universal design for learning in education and art.

Because the course is taken by a broad range of students from different disciplines with varying motivations and prior knowledge of the related content, I wanted to incorporate more content flexibility in the course design. I also wanted to structure the course so that there would be multiple types of media through which students could engage with the material. The course incorporated options for videos, articles, shorter articles, and articles incorporating similar content but written more in plain language. Students also had thematic options related to content. Students could build weekly emphasis on readings that might be more focused on teaching practices, museums and art spaces, theoretical disability studies, disability studies and artistic practice, and more, as well as some required common readings. From there, they could build their own “menu” across many additional options.

A course Padlet™ site was developed as a flexible and growing space for organizing related online content around the course's key themes. Student contributions could also be added to our course Padlet, which became an extensive resource of relevant material across disability studies, art education, art spaces, disability justice, UDL, etc.

Image Caption: This work is by Aelim Kim, who was an on-campus Ph.D. student in AAEP. The work’s title is “Collection Organized According to an Invented Hierarchy.” 7604 is an artmaking course required for Online MA in Art Ed students, but it can be taken by all graduate students. The assignments incorporate a number of engagements with everyday materials. This assignment involved engaging with a “collection.”

However, this approach necessitates supporting students around their goals and key questions to identify and facilitate learning pathways from week to week. In prior in-person courses, I have used entrance and exit tickets as tools to facilitate student directed learning. In the online course design, as students completed one week of content and progressed to the next, they responded to some very basic prompts about what they had learned, where they would like to learn more, and what questions may have arisen for them in the process. I responded to their entrance and exit tickets and made some suggestions around what material might be of interest to them based on their goals, questions, and interests in the upcoming week. Also, within the entrance and exit tickets, students are posing questions. I gain a sense of their interests as individuals and as a class. I can also help them navigate questions about wanting to know more or offer information and additional guidance for questions related to a need for greater clarification.

Typically, my courses incorporate group discussion boards. However, with the students having some readings in common and others that were their individual choices, they also presented new ideas and connections to the class. This was interesting in that students became more inclined to bring things to the discussion board to share with the class that were not options that week but connected with that week's theme. Ultimately, I want to see a transition with students toward intrinsic motivation and excitement about what they are learning. When I see students sharing things they are finding on their own or other content they are thinking about with their course readings and media, this communicates to me as their instructor that they are motivated, interested in the content, and have a good sense of community as a class. My role as an instructor is integral to the motivation of my students and their engagement. In this class, I am very active on the discussion boards, modeling my tendency toward being curious about how an idea may connect to another example or resource. “This is a really interesting point you made about …. You might be interested in this….”

Making choices across a wide range of options is not necessarily easy for all students. Some need more mentorship and scaffolding to navigate decision making. By having students identify their goals and questions, the exit and entrance tickets become a way through which I can more specifically guide and mentor individual students. While we often think that how we respond to students' culminating assignments is the highest priority, in this redesign, I realized the importance of providing feedback as students are developing ideas and generating their interest as integral to online student motivation.

In terms of things that do not work...

When integrating technologies in a course design, I have to ask myself what a given application or tool offers a learning experience. For example, I had decided not to continue to use a particular technology in a class activity when it became clear that students were going to struggle too greatly with aspects of the application itself overshadowing what benefits it may have brought to the assignment.

Many synchronous types of activities do not always translate well into online learning spaces. One of the advantages of online learning course design is its ability to be innovative within asynchronous course designs. Again, this is an area where I would ask myself, what do I want students to learn and how might they demonstrate their understanding? Does this necessitate a synchronous activity?

A challenge will always be that things will stop working. Anything involving links, online content, and software application updates may result in broken links, formatting changes, etc. For example, Padlet updated its application at the end of the semester and altered my text formatting throughout all my entries. I will now have to address the issues that one update created.

Regarding things that do not work, I would also include things that are not digitally accessible. Moving through existing course designs, it is essential to attend to where digital technologies are not working at the most crucial level of access. Understanding accessibility more deeply in digital environments is essential and will require additional mentorship for faculty. Identifying where access issues may exist requires having a better sense of what fosters and limits digital accessibility. This is an area where we can become much more proactive in terms of incorporating innovative approaches to designing learning experiences that address digital accessibility.

Take advantage of the great resources at Ohio State across the ASC Office of Distance Education, OTDI, and the Drake Institute to better design distance education courses and impactful teaching in in-person and distance education courses. I have a background in education and work with current and future teachers. I have found that all my teaching benefits significantly when I creatively engage with designing distance learning opportunities. Effective distance education necessitates a deep understanding of teaching and learning.

A definite challenge with this course is that it is a 6-week course. The first few times that I taught the course, I continued to shift what I might emphasize in the curriculum. For example, I recognized that without enough foundation in disability studies, students tend to apply UDL in ways that were not adequately challenging students' existing assumptions about disability. However, when I switched to incorporating texts on disability studies, these were too remedial for some students and too challenging for others and for some, too much about education…. However, amidst concerns about students' understanding of concepts, content, and how they applied their understanding, I was also concerned that the course did not adequately model UDL to the depth I wanted students to understand.

Dr. Richardson eloquently highlights and reinforces one of the most critical mechanisms to effective and engaging course design for distance learning: flexibility. As the landscape of higher education continues to expand to reach broader and more diverse populations of learners it is vital that we keep focus on the mission of bringing robust and fulfilling learning experiences to all, minimizing exclusion and frustration. As Dr. Richardson rightly highlights, flexibility and access go hand in hand toward cultivating positive and meaningful learning.

ASC ODE agrees with Dr. Richardson that this also means that navigating the digital landscape presents lots of unique concerns for flexibility, such as staying ahead of technological elements that might "break" from time to time. This is why we continue to advocate for a productive, cooperative relationship between instructors and support staff, like our Instructional Design team, where we can work together toward creating the kind of learning experiences and environments that offer the greatest potential for innovation, engagement, and access.

We want to express our gratitude to Dr. Richardson for agreeing to participate in our Instructor Spotlight series. They were also featured as a panelist one of ASC ODE's teaching forum events, "Accessibility: Beyond the Basics." More information about this event, including a recording, can be found by following the link to the event page above.

If you are interested in nominating an outstanding instructor who has invested in developing and delivering online courses, please feel free to email ascode@osu.edu using the subject line Instructor Spotlight Recommendation. Explore the full catalog of Instructor Spotlights here.