Increasing Motivation and Maximizing Student Engagement: The Benefits of Gameful Learning

Gameful Learning employs a series of evidence-based psychological approaches to create a learning environment that supports a combination of students’ intrinsic motivators – those motivators that are self-determined, carry internal value for the individual, and lack the need for external influence – and the extrinsic motivators that allow for the greatest sense of autonomy and self-determination.

Keywords

- Gameful Learning

- Motivation

- Student Engagement

- Assessment

- Varied Assignments

- Transparency

- Metacognitive Explanations

- Community Building

- Educational Technology

What motivates learners?

Have you ever commented or heard another instructor remark that some students are simply unmotivated or just want to take the easy way out? When we see a frequent lack of engagement from our students, it is easy (and perhaps natural) to conclude that the absence of participation stems from disinterest, laziness, or a lack of motivation on the part of the student. However, a wealth of empirical, psychological research refutes this common misconception. Research demonstrates, instead, that human beings, at their core, are inherently motivated to put forth effort and to act; yet certain social contexts and cultural or developmental influences can affect an individual’s level of motivation and even derail that motivation all together if the appropriate supports are not put into place[1]. As Rachel Niemer and Barry Fishman deduce in their edX course on Gameful Learning, everyone is motivated by something. They just may not be motivated by the same things or to do the same things you want to do.[2] So how do we identify what motivates students? What can we do to capture their attention, regardless of the subject at hand or a student’s background, and keep them engaged over an extended timeframe? This is where exploring the structure of games, the foundational principles of game development, and the ability of games to speak to a player’s intrinsic motivators – those motivators that are self-determined, carry internal value for the individual, and lack the need for external influence – come into play.

What are games and why are they so appealing?

Games have continued to grow in popularity in recent years, among both teens and adults. Between 80 and 90% of teens over the past decade have reported playing games on a regular basis[3]. But what is it that games offer these players that makes them so appealing? A game consists of a system of players, artificial conflicts, rules, and quantifiable outcomes. Games offer a series of challenges that are achievable given an appropriate amount of support and helpful feedback. The best games encourage productive failure, autonomy, and exploration, especially by creating a sense of belonging. Sound familiar? Education and games share several fundamentals, and that is why concepts such as Gamification — or the employment of games in the classroom — have become popular topics in recent years among instructional designers, curriculum developers, and instructors alike.

The idea behind Gamification is to transform educational materials into fun, interactive, and compelling content that encourages and boosts participation by using games. And while the use of Gamification in an educational setting has shown evidence in its ability to increase student engagement when employed correctly, creating a successful educational game is not an easy task. To do so often requires a significant amount of time, money, technical support, and effort that many instructors do not have at their disposal. As a result, the conversation around the role of games in the classroom has shifted towards a slightly different concept and practice that follows the principles of Gamification, but that does so with less effort by building upon the types of instructional practices that successful instructors have already been using in both classroom and online education.

What is Gameful Learning and how is it different from Gamification?

Unlike Gamification, the premise behind Gameful Learning is not to play games in the classroom, but instead to utilize the basic principles of successful game design to create better learning environments and to encourage the types of behaviors that move students toward a state of flow. That is, a state of learning where engagement is seamless and not forced. At its core, Gameful Learning attempts to transform traditional activities, assessments, and classroom structures by incorporating course design elements that support students’ intrinsic motivators. Gameful Learning bases its approach on a range of psychological, motivational theories that have demonstrated a clear link to an increase in overall student satisfaction and achievement across a variety of learning environments, regardless of cultural background. Furthermore, the use of gameful design in the classroom has shown great promise in its ability to support the most at-risk students by establishing a level of engagement that has the potential to overcome some of the barriers and disincentives that such students might otherwise face.[4] In other words, the goal of Gameful Learning is to create a learning environment that incorporates and supports the types of motivators that keep students of all backgrounds engaged and committed to learning.

Ryan and Deci identify three primary types of motivation:

- Amotivation: a complete lack of action or lack of intent to act by an individual that often results when one does not see the value in a given activity or when one feels incapable of completing the task at hand

- Extrinsic motivation: relies on some form of external control or reward to regulate one’s behavior and desire to act; the manner in which extrinsic motivation is regulated can occur over varying degrees of autonomy

- Intrinsic motivation: arises from strongly held internal values and appears in the absence of external regulation; it is self-determined and moves one to act out of interest, enjoyment, and natural curiosity[5]

Of these three types of motivation, intrinsic motivation is the one most associated with creating a space of optimal learning and enhanced student engagement, as it supports the three most basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness[6]. As Christopher P. Niemiec and Richard M. Ryan state, “when people are intrinsically motivated they play, explore, and engage in activities for the inherent fun, challenge, and excitement of doing so.”[7] At the same time, however, these researchers acknowledge that much of what people do is not intrinsically motivating, especially in an educational environment. Instructors, therefore, cannot rely solely on students’ intrinsic motivation and must find ways to also support those extrinsic motivators that allow for the greatest sense of autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Gameful Learning practices offer one tool that can help instructors do just that by creating a learning environment that incorporates activities, assessments, and an overall classroom structure in which the often necessary external regulations or controls can still take on personal value for the individual learner.

What evidence-based approaches support Gameful Learning?

Gameful Learning employs a variety of methods, in a manner very similar to excellent game design, that support the types of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators proven to establish optimal learning environments. A gamefully designed course consists of clear learning goals, appropriate levels of challenge, student autonomy, relatedness, competence, productive failure, practice, and reinforcement[8]. All of these strategies stem from a series of motivational theories that promote evidence-based practices to support intrinsic motivation and the more autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation. The basic descriptions of three of the most referenced motivational theories in discussions surrounding Gameful Learning are highlighted below.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) an approach that explores the social environments or contexts that create differences in motivation and personal growth. It is especially concerned with the three inherent psychological needs: 1) Autonomy or the freedom from external controls, 2) Competence or the quality or state of having sufficient knowledge or skill, and 3) Relatedness or a connection by way of an established or discernible relation. When all three of these needs are satisfied, both self-motivation and mental health have been shown to improve. The theory also addresses the ways in which non-intrinsically motivated behaviors can become more autonomous and self-determined with the right support, as well as the ways in which a variety of social environments can impact such behaviors and processes.[9]

Expectancy-Value Theory argues that the amount of effort that learners put forth towards a given task, the educational choices that they make, and their overall performance on a task or in a given subject are dependent upon how likely they believe they are to succeed and how much they value that activity or subject. The theory relies on both the learner’s perception of their current level of competence – often shaped by previous experiences and social influences – and on their future expectancies for how difficult they believe a task will be to successfully complete. Eccles and Wigfield found among adolescents that “the effects of previous performance on current performance are mediated through children’s ability and expectancy beliefs.”[10] In other words, children’s beliefs and expectancies in terms of their ability to succeed in a particular subject such as math have shown to more strongly predict their performance outcomes than past grades and achievement. Even if students previously performed poorly in a subject, if the new learning environment has supports in place to bolster students’ confidence and ability beliefs from the beginning, they are more likely to put in effort and succeed, regardless of their past experiences.

Achievement Goal Theory is a social-cognitive theory that began in the 1970s and that continues to evolve and inspire debate as a result of a long history of conflicting definitions. The theory generally explores two primary types of achievement goals: 1) mastery, learning, or task goals with the purpose of developing competence and skills and 2) performance, ego, or ability goals with the purpose of demonstrating competence, especially through social comparisons. The performance goals have further been broken down into performance-approach goals in which learners seek to demonstrate a high level of ability and performance-avoidance goals in which learners avoid displaying a low level of ability. Though much of the research findings remain ambiguous, certain trends have appeared over hundreds of studies. Those trends generally show that 1) mastery goals are most associated with interest and positive emotions, along with more deeply-invested learning strategies, 2) performance-avoidance goals are often associated with negative emotions and can lead to student disengagement following failure, and 3) performance-approach goals are often linked to higher achievement but can result in either positive or negative emotions, as well as learning strategies that may or may not be well-suited to the learning environment. One potential benefit of this theory is its continued concern for questions about culture, identity, and context and how achievement is both valued differently and can mean something different within these varied environments.[11]

What does a Gameful Learning environment look like?

Student choice, ongoing feedback, monitored progress, and a reduced fear of failure are the primary elements that differentiate a gameful learning environment from a traditional one. The way in which content is taught or presented between the two, is generally the same. The adjustment, instead, occurs in “the fundamental classroom assessment systems…simultaneously increasing the opportunities for students to have autonomy and mitigating the impact of failure, such that learners are empowered to exert effort in spaces that they might otherwise have avoided.”[12]

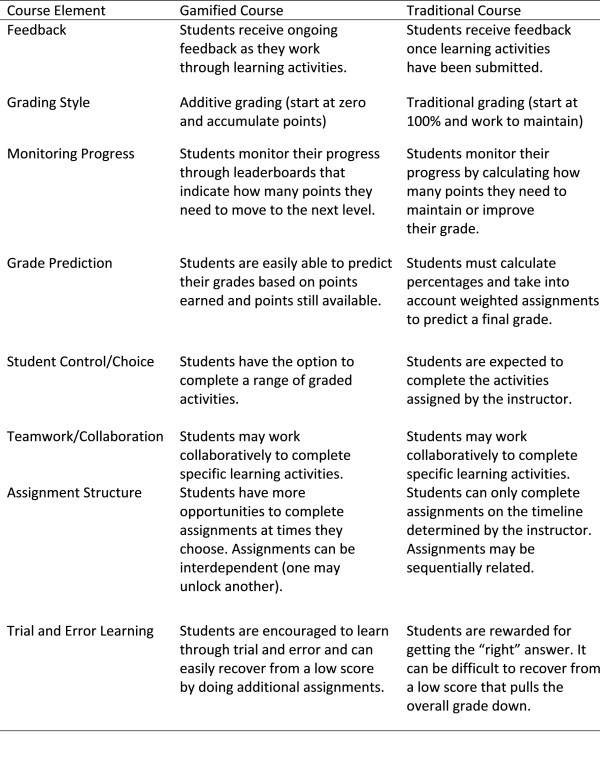

In Table 1 below, Brunvand and Hill identify eight key course elements and highlight how the structure of those elements compare and contrast between a gamefully designed course and a traditional one.[13]

Table 1 - Gamified vs. traditional elements

Is Gameful Learning the right approach for every course?

Gameful Learning is not a one-size-fits all approach, nor should it necessarily be used in every educational instance. In fact, Gameful Learning environments should look very different from one class to the next as its primary purpose is to cater to the psychological needs of the students that make up a given environment. And though such a design practice does not necessitate a new instructional approach or even an entirely new set of assignments, proponents of Gameful Learning acknowledge that its implementation does require some additional strategic planning and methodical analysis, especially in “the restructuring of assignments and rethinking how grading is done.”[14]

In considering whether or not Gameful Learning is the right approach, Brunvand and Hill offer a helpful model and series of questions that should be thoroughly evaluated by instructors before deciding to begin the switch to a gameful course:[15]

- Pedagogical Objectives: Does gamification fit with your goals and objectives for the course?

- Tech Competency: Are you comfortable using technology in your teaching?

- Content Fit: Does the content of the class lend itself to gamification? (Consideration: The course content lends itself to flexibility and choice. Learning objectives can be met by offering students a variety of assignments. While there may be some structured assignments that all students must complete, many of the learning objectives could be met by way of a diverse range of assessment types.)

If the answer to each of these three questions is yes or maybe, then Gameful Learning may be an appropriate choice and should be considered as a viable means for improving the overall course learning environment and student engagement.

How do I begin to transition to a gamefully designed course?

Though it may initially seem like a daunting task, there are a wealth of tools, tips, and simple changes that already exist to help instructors begin to establish a Gameful Learning space that can enhance student engagement and learning. The first step is to define the course learning objectives and goals and to create a range of assignments that offer students the ability to demonstrate their knowledge and attainment of a particular objective. Once a set of possible assignments and assessments has been created, the second step is to establish a system to monitor course progress. This step primarily involves determining how and when regular feedback will be given and providing clear instructions that enable students to easily determine which assignments they want to complete to earn the grade level they desire. The third and final step is to strategically determine the point scale or to weight the assignments in a way that prevents students from completing only the easiest or minimum amount.[16] In addition to these three key components in gameful course development, there are a range of other incentives and additions that an instructor might consider incorporating, such as badges, identity play, locks and unlocks, etc.

We invite you to consider employing Gameful Learning elements in your own courses and to gather inspiration for how you might start making some simple changes in your course design by exploring the additional resources provided below.

Key strategies and techniques of Gameful Learning courses that increase student participation:

- Use a leveling up grading system

- Offer flexibility and variety of assignments

- Allow student input on or co-creation of assignments

- Clearly state the learning goals and rationale for assignments and tasks

- Create a community between students and between student and instructor

- Provide frequent and timely feedback

- Encourage exploration and recognize failure as a learning moment

- Use embedded assessments

- Foster identity play

Additional resources and useful tools

- For helpful tips on how to get started with Gameful Learning, planning resources, and examples of gamefully designed course syllabi check out Gameful Pedagogy: Going Gameful

- Ten Ways to Support Student Autonomy

- Buckeye Badges

- Hypothesis

- U.OSU

- ASC Carmen Template

Citations

[1] See Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci, “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being,” American Psychologist 55, no. 1 (January 200): 68-78.

[2] “Leading Change: Go Beyond Gamification with Gameful Learning,” edX course, originally launched March 6, 2017, https://learning.edx.org/course/course-v1:MichiganX+GL101x+3T2020/home.

[3] For more details about the statistics of game play, especially among teens, see Andrew Perrin, “5 facts about Americans and video games,” Pew Research Center (September 2018), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/17/5-facts-about-americans-and-video-games/ and Jane McGonigal, “Position Statement: I’m Not Playful, I’m Gameful,” in The Gameful World: Approaches, Issues, Applications, ed. Steffen P. Walz and Sebastian Deterding (The MIT Press, 2015), 653-657.

[4] For more about Gameful Learning and a brief discussion about its potential to support at-risk students, see Kevin Bell, “Gameful Design: A Potential Game Changer,” EDUCAUSE Review May/June (2018).

[5] Ryan and Deci, “Self-Determination Theory,” 68-78.

[6] For further discussion on the three basic psychological needs see Ryan and Deci, “Self-Determination Theory,” 68-78 and Christopher P. Niemiec and Richard M. Ryan, “Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom: Applying Self-Determination Theory to Educational Practice,” Theory and Research in Education 7, no. 2 (2009): 133-144.

[7] Niemiec and Ryan, “Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness,” 134.

[8] “Leading Change.”

[9] For an in-depth discussion and analysis of Self-Determination Theory see Ryan and Deci, “Self-Determination Theory,” 68-78.

[10] Jacquelynne S Eccles and Allan Wigfield, "Expectancy Value-Theory of Achievement Motivation," Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (2000): 68-81.

[11] For an in-depth discussion of the evolution of achievement-goal theory see Avi Kaplan and Tim Urdan, “The origins, evolution, and future directions of achievement goal theory,” Contemporary Educational Psychology 62 (2020): 1-10

[12] Stephen J. Aguilar, Caitlin Holman, and Barry J. Fishman, "Game-Inspired Design: Empirical Evidence in Support of Gameful Learning Environments," Games and Culture 13, no. 1 (2018): 45.

[13] Stein Brunvand and David Hill, “Gamifying Your Teaching: Guidelines for Integrating Gameful Learning in the Classroom," College Teaching 69, no. 1 (2019): 59.

[14] Ibid., 68.

[15] Ibid., 60-64. For a visual of this modeling process and the steps for getting started with Gameful Learning, see the chart on page 60.

[16] For detailed steps and guides on how to get started with Gameful Learning see Brunvand and Hill, “Gamifying Your Teaching,” 58-68 and Gameful Pedagogy, "Going Gameful.,” accessed September 23, 2021, https://www.gamefulpedagogy.com/getting-started-with-gameful-course-design/.